TRanslations of time

An Interview with Boris Dralyuk

How can we connect with bygone poets and make their words resonate today? In his debut collection My Hollywood as well as in his Russian translations, Boris Dralyuk explores this question and succeeds. Through an interplay of ever-present loss, happenstance, and humor, the work is a meeting place between artists past and present; between a real person and other real people he admires. “I’ve always known that one can’t dwell in the past,” Dralyuk writes. “But that doesn’t stop me from dwelling on it. It does hold lessons for us, cautionary tales. And it holds its treasures – among them verbal objects that seem as alive to me as anything uttered this very minute, perhaps more so.” Another key to his practice is form: not only does it add integrity to the work, he tells us, but through structure we can find surprise.

Can you tell us about your process and path towards creating your new collection, My Hollywood?

I’d be happy to, though of course the path was anything but smooth and straight. Some of the poems I included are much older than others, and I only came to see them as parts of a potential whole after I’d written the newer ones. I’ve always liked shorter collections, in which shifts in tone and subject are palpable, even if subtle. A reader can linger over individual poems a bit, yet still make it through the book quickly, at least the first time around, forming and retaining an impression of – or a feeling for – the whole, with its ups and downs, twists and turns.

The book has four sections. Once I’d written a number of the poems from the titular section, “My Hollywood” – all of them drawing on my life in the neighborhood and on its history – I decided that I would follow it with a section of poems more abstract in their subjects and moods. Varied though they are, these poems all concern alienation, as well as the attempt to overcome it, and they end with a trio of lyrics inspired by long-gone Russophone poets. That leads into a section of translations from Russophone poets who lived out their days in Los Angeles – translations that take us back to Hollywood, but also resonate with the themes of alienation in the preceding section. And I close with a section that mingles all these themes and approaches, composed largely of homages and farewells.

“I find the treatment of serious subjects can grow more poignant and memorable when leavened by a dash of whimsy; the effect is somehow fuller, truer to my sense of how the human mind works. One has to be careful, of course: too much whimsy and the meal is ruined. But if the measurements are just right, you’re really cooking.”

What drew you to the voices of bygone artists that you wove into your work? How did you integrate them with your own identity?

I feel I’ve always been drawn to the work of those who came before me. The past has always seemed an enclosed world, unchanging, and therefore safe, even if tragic. I’ve always known that one can’t dwell in the past – pace Faulkner, it’s over – but that doesn’t stop me from dwelling on it. It does hold lessons for us, cautionary tales. And it holds its treasures – among them verbal objects that seem as alive to me as anything uttered this very minute, perhaps more so. This is one reason I became a translator, to revel in the liveliness of those old voices. In his canny essay on “The Poet as Translator,” Kenneth Rexroth writes that “translation saves you from your contemporaries”: “All through the world’s literature there are people I enjoy knowing intimately, whether Abelard or Rafael Alberti, Pierre Reverdy or Tu Fu, Petronius or Aesculapius. You meet such a nice class of people.” Sometimes you sense the kinship immediately. You commune with them long enough and they become part of you.

When I translate a poem or piece of prose, I build a voice that, to my ear, matches the voice I find in the original. I sink into that voice, like an actor. But in order to build that voice in the first place I must not only understand but empathize with the original speaker. Communing is really the word for it. We all do this as readers; translators merely take it one step further, creating something new on the basis of that connection. I suppose I do this as a poet as well. I’m driven to connect with the artists I admire, to render not only the facts of their lives but the texture of their experience, which is the essence of it.

There’s an interplay of reliquary, loss, but also whimsy in your collection. Beyond just the subjects and stunning vignettes, the rhyme contributes to this sentiment. What’s your relationship to formal poetry?

I would say I’m an unabashed advocate of form, but in truth there’s a whisper of shame to my formalism – the shame that usually accompanies addiction. I love form – meters, rhyme schemes – because it helps me along, lending shape and integrity to thoughts I might otherwise dismiss as unworthy of sharing. As I’ve said elsewhere, rhyme can also reward us with surprises. Another thing form may foster is the quality you describe in your question: a complicated interplay of moods. I find the treatment of serious subjects can grow more poignant and memorable when leavened by a dash of whimsy; the effect is somehow fuller, truer to my sense of how the human mind works. One has to be careful, of course: too much whimsy and the meal is ruined. But if the measurements are just right, you’re really cooking.

Are there any upcoming projects or writerly dreams you could share with us?

For the past decade I’ve been working closely (or, to use that word again, communing) with the Russophone American poet Julia Nemirovskaya. At this point, every word she writes feels immediately familiar to me – I understand it intimately, from the inside. I’ve absorbed her attitudes, her vocabulary, her rhythms, finding or forging within myself their Anglophone equivalents. My versions of her poems and reflections on our collaboration have appeared in a number of journals, and our conversations with students at Bryn Mawr was recently published by World Literature Today. I think it’s high time for us to put together a collection. In fact, the collection is ready, awaiting the right publisher.

I have a few other translation projects lined up, but I also hope to piece together some of my versions of poems and songs from my hometown, Odessa, Ukraine, into a book on this jewel of a city and its spunky scribes. The book would be a companion piece to my translations of Isaac Babel’s stories, a selection of which will soon appear under the title Of Sunshine and Bedbugs from Pushkin Press, which also published Odessa Stories and Red Cavalry.

I’m working on poems, too, little by little. Oh, and my wife and I are expecting two little ones any day now. Who knows what they might inspire?

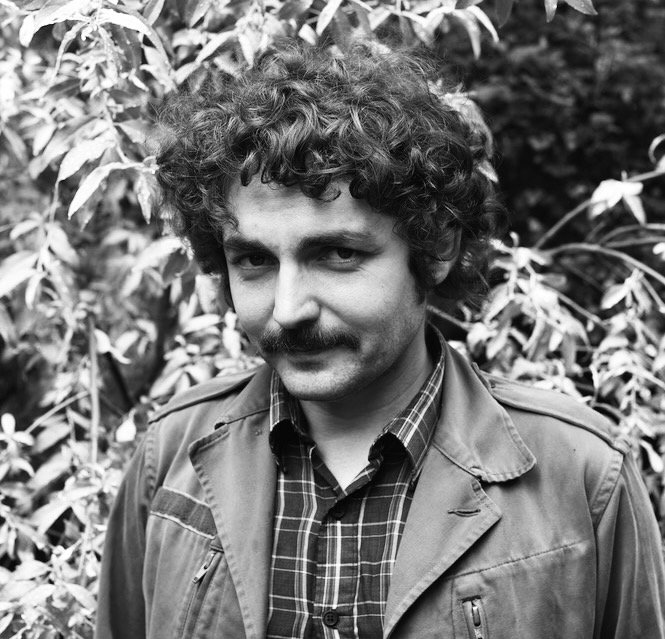

Boris dralyuk

Boris Dralyuk is a literary translator, poet, and the Editor-in-Chief of the Los Angeles Review of Books. He holds a PhD in Slavic Languages and Literatures from UCLA, where he taught Russian literature for a number of years. He has also taught at the University of St Andrews, Scotland. His work has appeared in the Times Literary Supplement, The New York Review of Books, The New Yorker, London Review of Books, The Guardian, Granta, and other journals. He is the author of Western Crime Fiction Goes East: The Russian Pinkerton Craze 1907-1934 (Brill, 2012) and translator of several volumes from Russian and Polish, including Isaac Babel’s Red Cavalry (Pushkin Press, 2015) and Odessa Stories (Pushkin Press, 2016), Andrey Kurkov’s The Bickford Fuse (Maclehose Press, 2016), and Mikhail Zoshchenko’s Sentimental Tales (Columbia University Press, 2018). He is also the editor of 1917: Stories and Poems from the Russian Revolution (Pushkin Press, 2016), and co-editor, with Robert Chandler and Irina Mashinski, of The Penguin Book of Russian Poetry (Penguin Classics, 2015). His collection My Hollywood and Other Poems will appear from Paul Dry Books in April 2022. He received first prize in the 2011 Compass Translation Award competition and, with Irina Mashinski, first prize in the 2012 Joseph Brodsky / Stephen Spender Translation Prize competition. In 2020 he received the inaugural Kukula Award for Excellence in Nonfiction Book Reviewing from the Washington Monthly.

Photo courtesy of Jennifer Croft